Repositioning The Court

Approximately 80% of the population of Rikers Island are detainees that have not been convicted of a crime and are awaiting trial. Kalief Browder was a detainee on Rikers Island and his arrests and time spent incarcerated without a conviction exemplifies how the current system is broken. Kalief was arrested twice, about 8 months apart. The first time he was not detained after the night of his arrest and during his court appearance he was charged and plead guilty to a crime in which he was a bystander. He given probation as his sentence. The second time, Kalief was arrested a few days after the alleged crime and he maintained innocence in court. Since he was on probation at the time of the second arrest, he was given a high bail which he and his family could not pay. He was then taken to Rikers Island for detainment.

People usually don’t stay in Rikers as long as him, because people plea out. In 2011 the Bronx Criminal Court only 165 people with felony charges went to trial, while nearly 4,000 pled guilty. Fewer felony defendants have been going to trial than they have historically. This is in large part due to mandatory minumums and sentencing guidelines which ultimately give the prosecution more power in the court than the judge. Essentially the prosecution determines the sentence length because the charges they file already have sentence lengths attached to them. So, who are these people that are being detained currently? 89% of Rikers Island detainees are black or latino while only 53% of New York City residents are Black or Latino. The majority of the detainees are too poor to pay bail, even if the amount is a couple hundred dollars. The maps below look at the connection between race, poverty, and historic disinvestment by comparing the 1938 Redling Map with 2010 per-capita income levels in New York city and mapping the intersections of race and wealth.

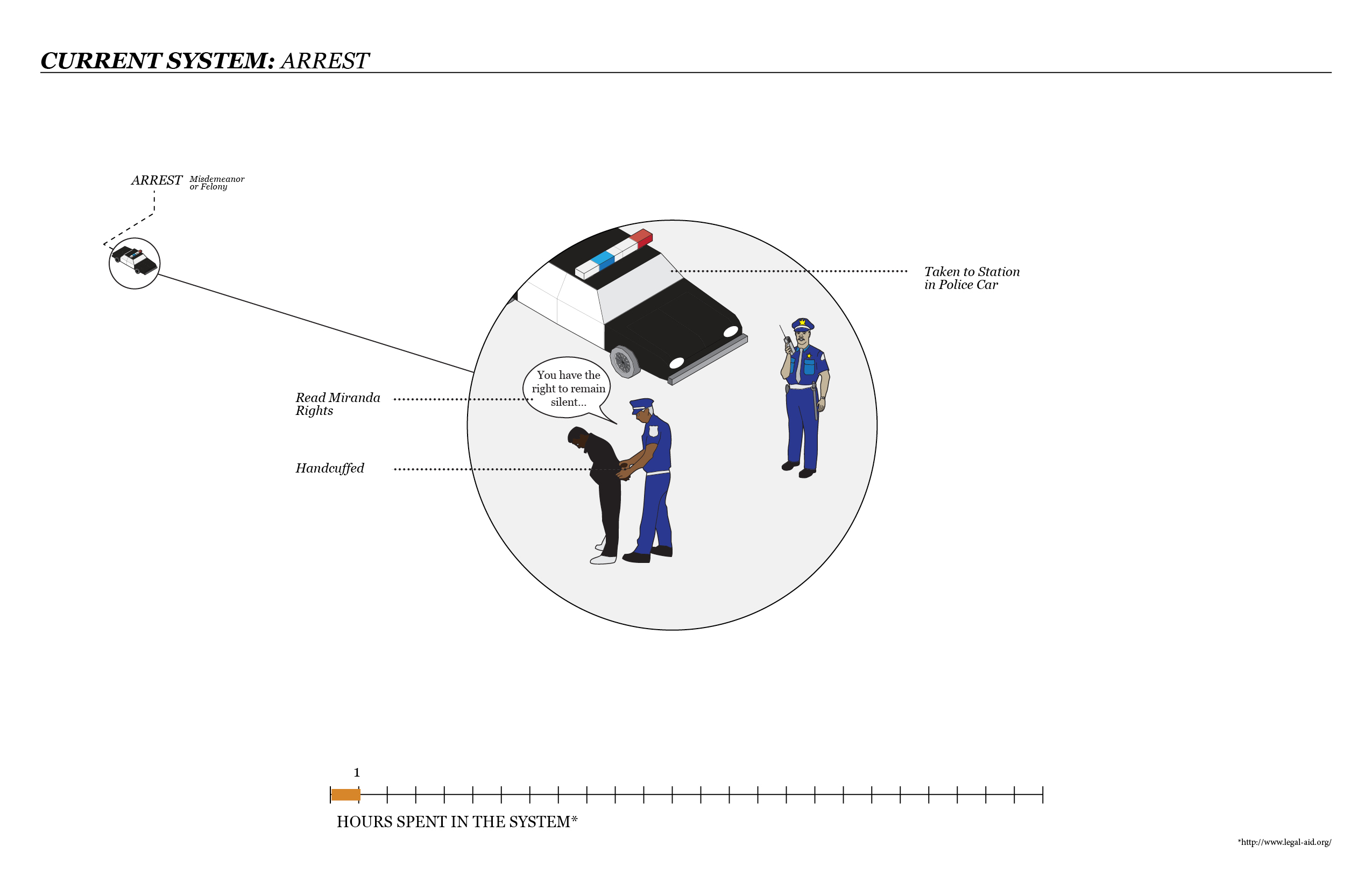

Urban environments in disinvested areas predispose arrest. During detainment one's health and opportunities decrease. While one’s physical health might improve after release, mental health takes a long time to heal. If the arrested person pleads guilty, they then have a mark on their record which prevents them from education and career opportunities. We should understand that the moment of arrest is the moment at which the failure of the system of governance is revealed and an opportunity to engage with citizens who need the services that often have historically been denied to them.

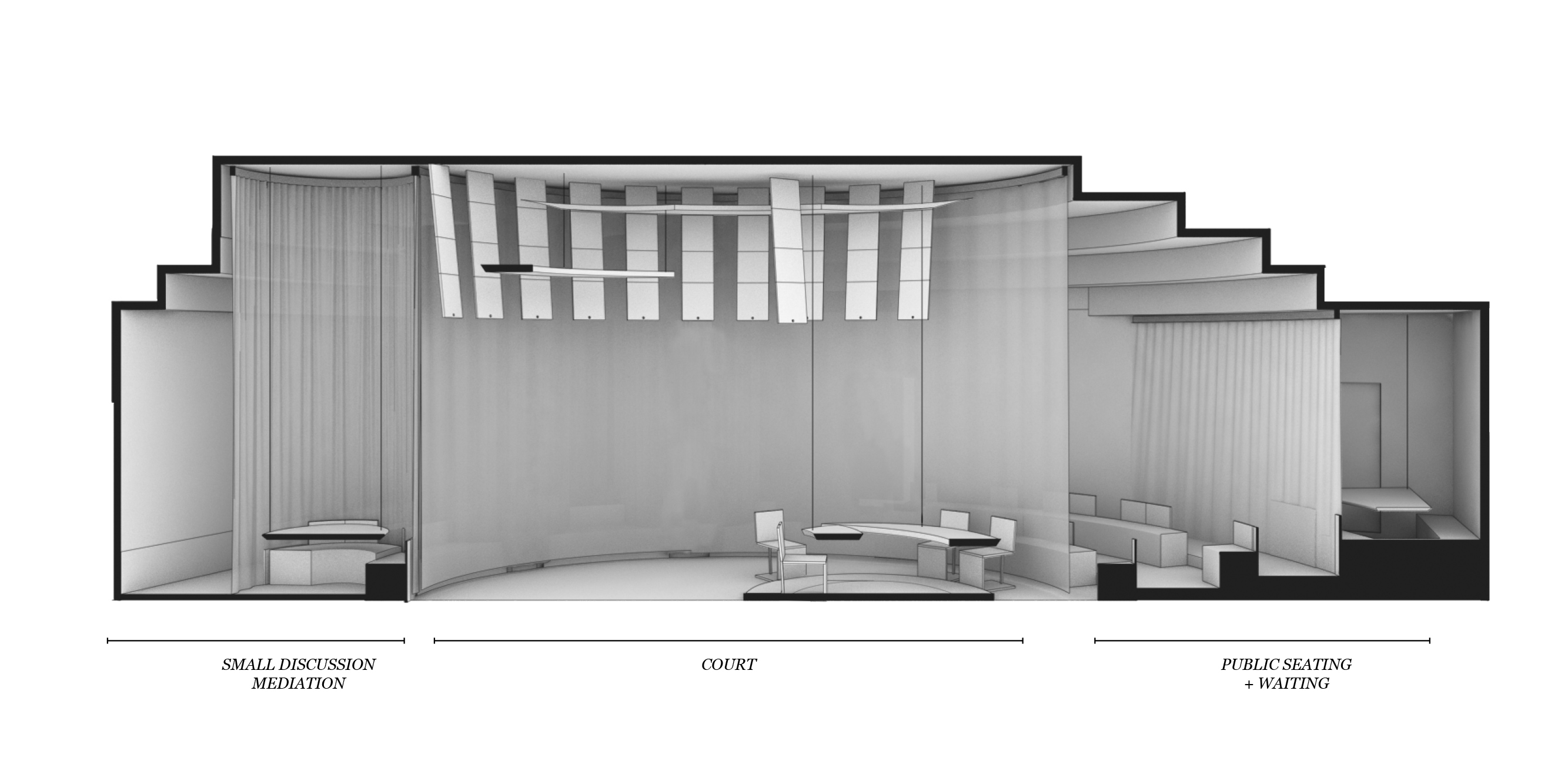

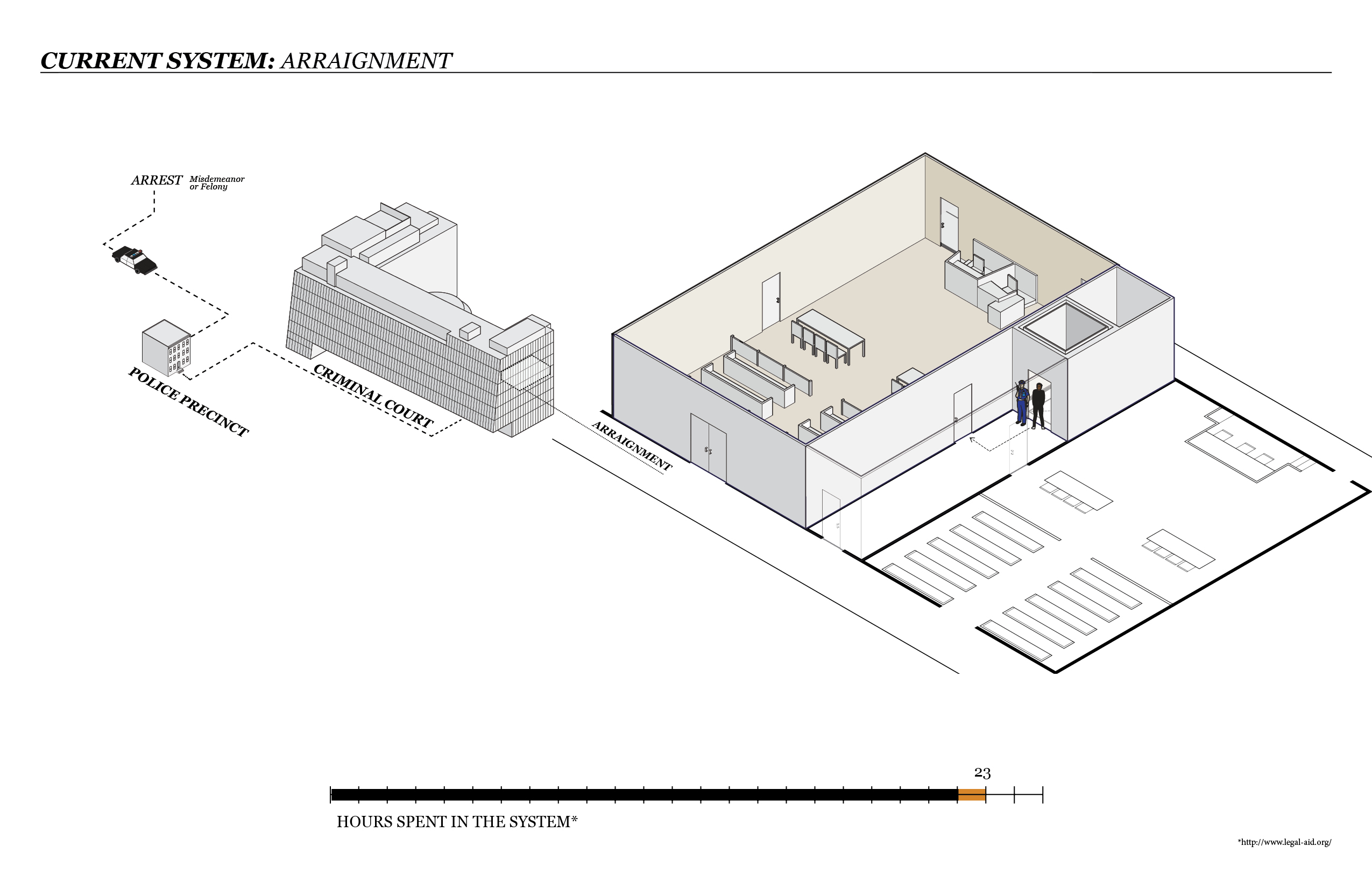

Traditional misdemeanor and felony courts are located in all five boroughs. Newer community courts are more dispersed and cater to one or two precincts rather than an entire borough. There are many non-profits operating outside the court that are trying to provide alternatives to incarceration and to divert people considered “low risk,” have mental health problems, or drug issues into services. However theses services are usually engaged as part of a plea or a sentence. While community courts are ideal, there are few, and often they come too late in the process to assist in diverting people. Mediation is now provided as an alternative adjudication method, however there are inadequate spaces for this to take place. The most progressive diversion program is L.E.A.D which is fully functional in only five cities. This program depends on communication between social workers, police officer, prosecution, and community members to identify individuals whose crimes are a product of their own drug addiction or due to prostitution. This allows for early identification of potential arrestees who would benefit from services and diverts them from the incarceration system completely. In the first 24 hours after arrest, an individual should have the opportunity to be diverted into a program that helps them, rather than deferring the course of action until a later court date. The rigidity of the current criminal justice system is designed with an equally rigid architectural logic that does not allow for flexibility of process.

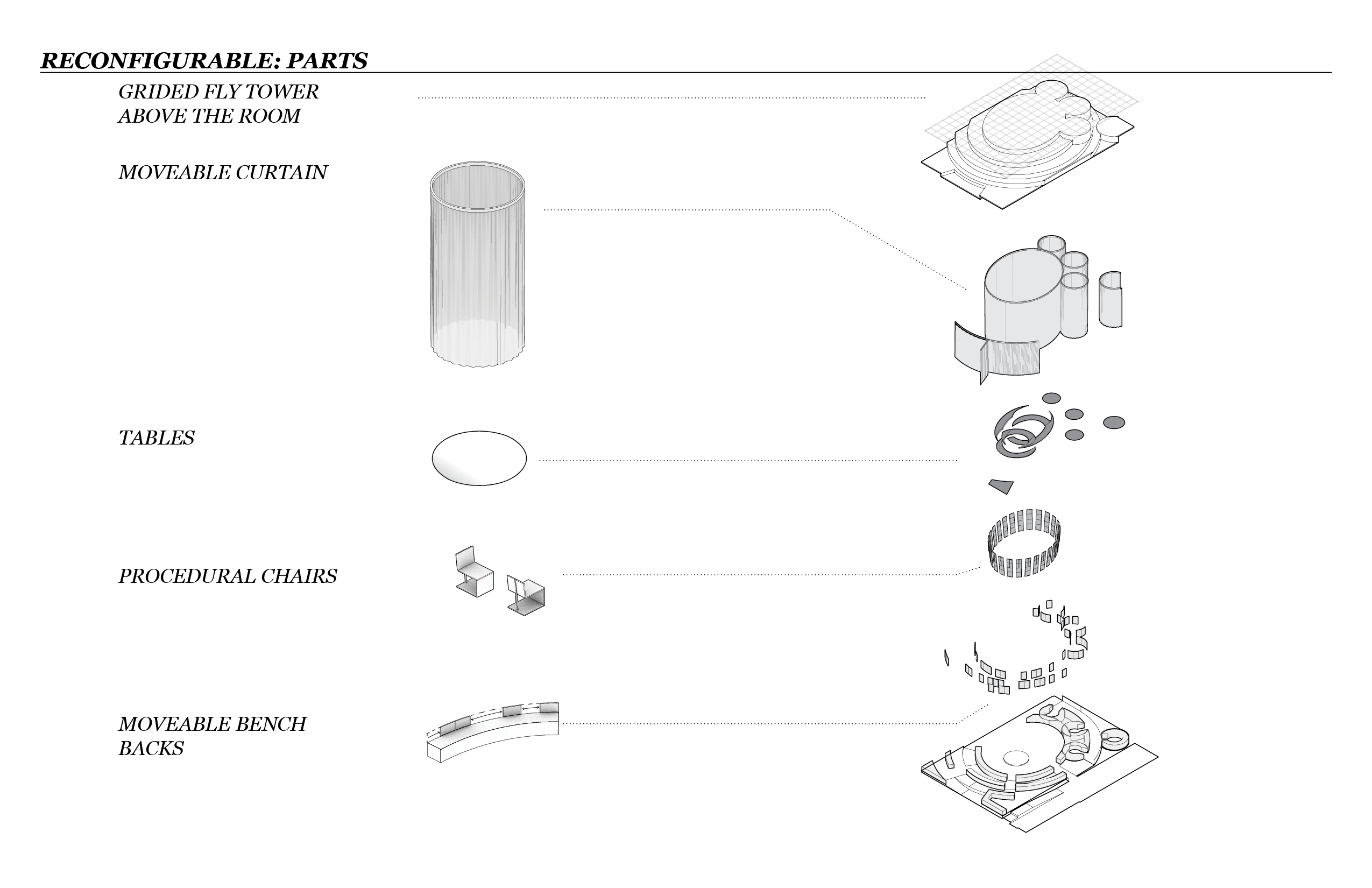

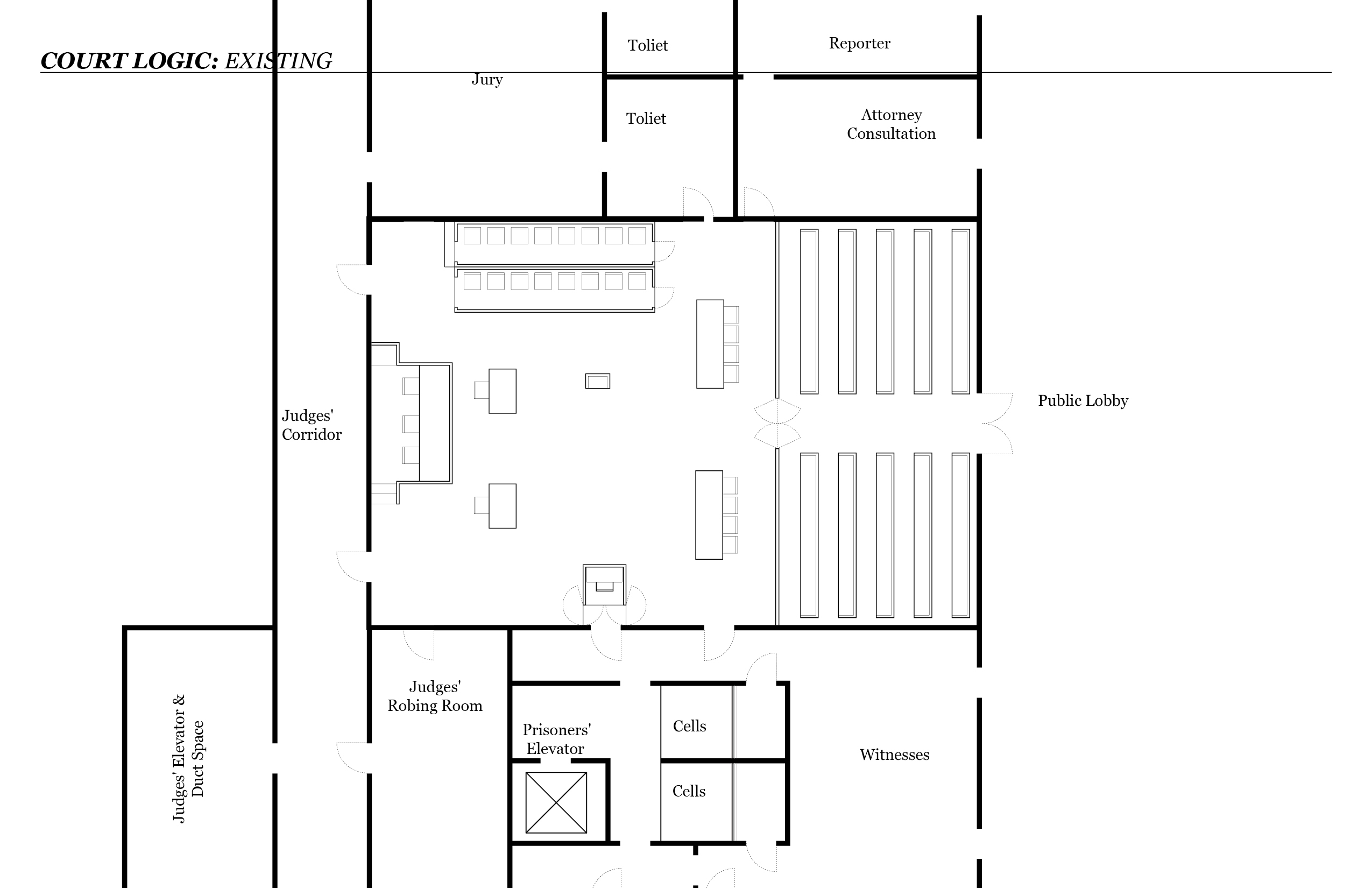

Architecture in the court enforces roles for certain procedures through positioning of bodies within a space— the direction they face and the height at which they sit as well as whether they are stationary or itinerant positions. Within the temporal space of a trial, persons inhabit the same space with the same roles over days, months, or years. The repetitive inscription of the roles into the space reaffirms the legitimacy and normalcy of the procedure. The dense and heavy furniture of the courtroom, regulated within the Standard Level Features and Finishes for US Courts Facilities by the US General Services Administration, naturalizes the intractability of the procedure and the inflexibility of the process. The architectural logics that support traditional power dynamics within a courtroom can be redeployed, to negate the traditional hierarchy of the existing system. Reorienting the heights of the roles, their furniture, and their positions relative to each other while including existing roles that currently happen outside of the arraignment process can provide space for other outcomes than pleas deals or years of detainment.